On a spring afternoon in 2016, at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles during the E3 videogame event, I crossed the stage between a packed house and a symphonic orchestra, to conduct an original theme I had written that had never been heard publicly. Even before the game’s title was revealed, the audience experienced a sweeping, symphonic score featuring Nordic folk instruments, choir, and strong, melodic themes. After my overture, the curtains parted and a vision of an older Kratos stepped out of the shadows, announcing that a new entry in PlayStation’s blockbuster God of War series was on the horizon, one which aged the character and promised a more mature narrative. The game launched in 2018 to universal critical acclaim and fan enthusiasm, cementing the vengeful god Kratos and his son Atreus a place amongst the most beloved videogame characters of all time.

In the spring of 2019, I found myself again in the offices of Santa Monica Studio, for creative discussions regarding the game’s sequel, God of War Ragnarök. Here the game’s previous director, Cory Barlog, introduced me to this new game’s director, Eric Williams. Cory and Eric have worked together for years on this franchise, and I immediately sensed Eric’s shared passion for the material and depth of experience. Having read the script, the scale of God of War Ragnarök became clear. This ambitious sequel’s story expanded upon the intimate character drama between Kratos and his son Atreus by introducing at least a dozen new characters, across all nine realms of Nordic mythology. The set pieces and action scenes were even more bombastic, and yet, the dramatic arcs were every bit poignant as those from the first story. In order to musically support this ambitious new narrative, I would need to fill God of War Ragnarök with new musical themes. At the same time, they would need to be interwoven with my material from God of War (2018).

For that original game, I had jumped into the score with enthusiastic abandon, ready to completely reinvent the sound of the franchise to fit this entry’s more sophisticated tone. However, this time, I felt the pressure of writing music in the shadow of my own previous work. Gamers the world over had forged emotional connections to my musical themes, and my work had won several major videogame industry awards. The thought of expanding on these ideas – and daring to think I might improve upon them – exhilarated and terrified me.

I began composing God of War Ragnarök in the summer of 2019, fully aware that I was at the onset of a journey that would be among the most creatively challenging of my career.

Warning: the following contains moderate spoilers for God of War Ragnarök

New themes for new families

God of War Ragnarök is a story of fractured families struggling to reform. To support that story, I needed two additional themes to represent families that Kratos and Atreus would encounter on their journey.

Theme: Huldra Brothers

The Huldra brothers, Dwarves Brok and Sindri, were supporting characters in the last game. They provided support for Kratos’ weapons as well as delightful comedic relief, and a heartwarming story of estranged brothers who reunite. Their role in God of War Ragnarök was greatly expanded, and now gamers travel to their realm of origin, Svartalfheim. I needed to craft them their own theme, one which could also tell us something of Dwarven culture.

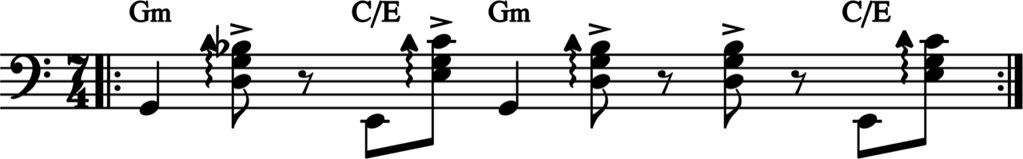

The Brok and Sindri Theme begins with a jaunty oom-pah ostinato performed on viola da gamba and nyckelharpa.

The jovial nature of the theme is colored by a signature rhythmic meter, 7/4, that provides an asymmetrical imbalance. The groove is bouncy, but also becomes increasingly heavy as their theme evolves.

The true charm for “Huldra Brothers” comes from the melody, featured prominently by a hurdy gurdy solo. (I am the credited performer of this solo, though I personally like to think we are hearing a character named Ræb playing their theme. More on him, later.) Their melody weaves around the asymmetrical meter with satisfying repeating patterns, featuring a “Scotch snap,” a frequent rhythm found in Scottish folk music.

The Huldra Brothers’ emotional B-Theme middle section implies there is more emotion to their story beyond mere comedic relief. And indeed, this theme evolves over the course of the story perhaps more than any other. At the end of their track, we hear their theme one last time, in a dark, melancholy cello solo – a shocking departure from the jovial tone at the beginning. Near the end of the soundtrack album, “Ræb’s Lament” is built around hurdy gurdy and orchestral variations of this melody. I will not spoil the narrative here, but suffice to say that if I did my job right, this comedic jaunty little tune will break your heart before final credits roll on God of War Ragnarök.

Theme: Ragnarök

The last primary new theme I composed for this game was for another family, representing the antagonists from Asgard, Thor, his father Odin, and the impending prophesied event of Ragnarök itself. To create a musical force that could threaten Kratos was a mighty task (his theme begins with powerful low male vocals that radiate menace and strength). To try to write a villainous theme that dwarfed Kratos’ in terms of strength and raw power was a fool’s errand. So, I looked to the script for inspiration.

Odin, as portrayed by Richard Schiff in God of War Ragnarök defies audience expectations. Eric Williams described him as a snake in the grass. He has a slight frame, and his vast power is most often implied. He is unafraid to use force, but would rather use psychological means to achieve his ends. Furthermore, I thought about the ominous impending doom of Ragnarök itself, which looms over the story’s horizon like a storm cloud. These ideas inspired me to energize the Ragnarök Theme with a slithering, dangerous, yet subdued ostinato. I wanted this string pattern to imply power and menace with a relentless triplet rhythm, one that rolls across the soundtrack like distant thunder.

This ostinato gets louder and louder as the story progresses. Above it, the main melody of the Ragnarök Theme offers a dark nobility and ominous foreboding, often sung by male choirs with an Old Norse text.

I spent about half a year sketching themes for this game, often tweaking back and forth with my creative partners at Santa Monica Studio. A few of them came easily, but several went through five or six drafts before I landed on something promising. I struggled especially with the Atreus Theme, as I found I was initially crippled by the intense pressure to write a theme that could measure up to my two most iconic melodies from God of War (2018). By the end, however, I was confident that my new themes for Atreus, Angrboda, the Huldra Brothers, and Ragnarök, would measure up to the melodies I had written for the last game.

Becoming Ræb

Scoring God of War Ragnarök was an expansion of everything that I had done in God of War (2018), culminating in one of the biggest orchestral scores of my career to date. However, my contributions to the game would go beyond the music.

Back in the spring of 2019, Eric Williams and Cory Barlog ended our first creative meeting about the project by showing me concept art. I was dumbstruck when I saw, at the bottom of the stack, a stout Dwarven fellow holding a beautiful hurdy gurdy, with a familiar, and perhaps even dashingly handsome face! At first, I thought the game’s brilliant art director Raf Grassetti had drafted a sketch of me as a Dwarf as a gift. I was further dumbstruck when Eric and Cory told me this image was no joke – this was a character named Ræb, who they intended to put into the game as a character that Kratos and Atreus would encounter in their journey, and that they intended me to perform the motion capture and provide voice acting for him!

Over two years later, in the summer of 2021, I stepped into PlayStation’s Santa Monica Studio not as a composer, but as an actor. I arrived at the motion capture stage, and the crew put little sensors all over my body and on my hurdy gurdy. I learned that my body movements were being captured by these sensors and instantly converted into animation data for my digital avatar.

Walking on to the stage, I was struck by how barren it looked – like an industrial warehouse with high tech equipment gathered around the edges of an empty space. Screens adorned the periphery, and when I looked at them I saw the real magic, a digital fantasy environment representing the tavern in Svartalfheim. Walking into the digital tavern, I noticed Ræb, and quickly realized he was walking because I was walking! I stopped, delighted like a kid playing with new toys, and started jumping around and flinging my arms, watching my digital avatar recreate my every movement in real time. It was like looking at a freaky fun house mirror where I saw a digital dwarf reflection of myself! I giggled uncontrollably as I moved my body and Ræb mimicked me.

To be an actor in a videogame, one must capture their motion, or do a mo-cap session. The crew told me that, typically, one or two sensors are placed on the hands to capture the motion of the arms, but that all detailed finger movement is typically animated later. However, because so much of my motion-capture work involved playing a musical instrument, they decided to try placing sensors on all of my fingers. They had never done this before! Sure enough, once they were done, I sat played hurdy gurdy and watched onscreen as the digital Ræb’s fingers rippled across his own hurdy gurdy keys, following my exact movements.

Recording the hurdy gurdy performance turned out to be the easy part. I also had to pretend to be in a crowded tavern environment, and to mimic the physical mannerisms that result from various interactions with Kratos and Atreus. I threw myself into the moment, and had as much fun as I possibly could, trying not to think about the potentially awkward reality that I was wearing skin-tight pajamas, covered in dots, pretending to be a dwarf holding a hurdy gurdy, in the middle of a room with people staring at me.

I loved the physicality of performing the motion capture. However, as fun as that was, it did not prepare me for the thrill of recording Ræb’s dialog a few weeks later. I worked with writer Matt Sophos, at a small recording studio in Los Angeles, who directed me through the vocal performances. Though I had never properly acted before, I found that my creative process as an actor working with Matt was the same as working as a composer with a director or producer when I am scoring narrative. In both cases, our shared goal is to make an audience feel something specific about what they’re experiencing. When I am a composer, I use notes, chords, and rhythms to achieve that goal. I quickly discovered that the only difference when I am an actor is that I use vocal rhythm, inflection, and tone to achieve the same goal.

I felt an electric thrill creating Ræb for God of War Ragnarök. The more I worked through the lines with Matt, the more I understood Ræb’s situation and in particular his feelings about Kratos’ companion Mimir. As I drove home from the recording studio, I was giddy, and my heart was pounding in my chest. I can safely say the few hours I spent recording Ræb’s dialog rank among the most exhilarating creative experiences of my life. While I don’t think I’ll quit my day job anytime soon, I would love the chance to explore this art form further!

To read more about my work on God of War Ragnarök, please check out the full blog post on my official site.

Bear McCreary: God of War Ragnarök’s composer details scoring its beautiful soundtrack

Source: Balita Araw

0 Comments